Process-Based Restoration

After two years of utter frenzy, where I’ve been too consumed by building habitat to get anything done on the publicity front, I’m finally getting around to a website rebuild. To better reflect what the business is about, I’ll be focusing more on what’s paying the bills: process-based restoration (PBR).

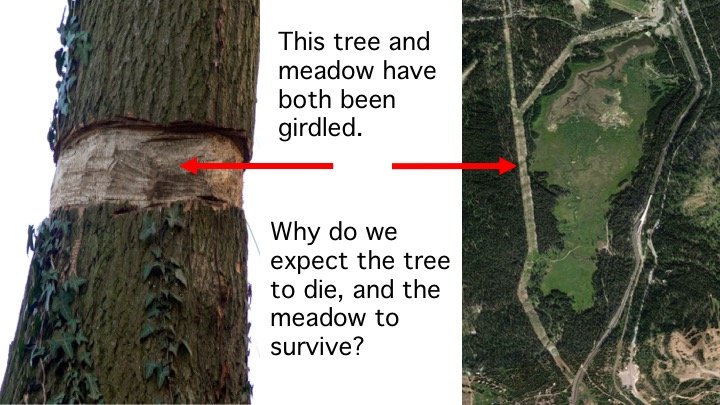

PBR is watershed restoration using stream power to do the work instead of diesel. Basically, our job is to be two-legged beavers.And there’s nothing complicated about most of it. We’re just using simple hand tools, some elegant design methods, and the massive free energy of stream power to drive system recovery. We start by addressing source problems, to ensure we’re actually treating the root causes of watershed degradation, rather than wasting money and carbon trying to manage symptoms.

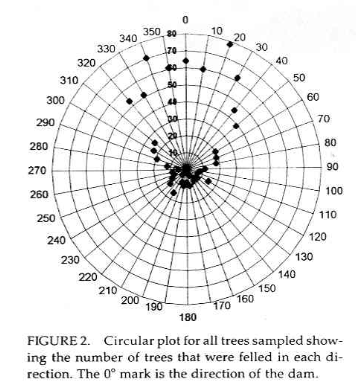

Then our job is to nudge the trajectory of the system back towards recovery, over time, with natural processes doing the heavy lifting. We do this by building structures that mimic naturally occurring wood jams and beaver dams, or reinforcing existing beaver dams. This additional material forces simplified stream systems to become more complex, start recruiting sediment, and reconnect to the floodplain.

Since the site provides both materials and energy for the build, PBR cannot be matched for pace, scale and efficiency. By using ecosystem power instead of diesel, we can build a mile of stream in under a week, for 50 thousand dollars and ½ barrel of oil

Since the site provides both materials and energy for the build, PBR cannot be matched for pace, scale and efficiency. By using ecosystem power instead of diesel, we can build a mile of stream in under a week, for 50 thousand dollars and ½ barrel of oil

That’s really exciting, because most of California’s stream miles are 1st and 2nd order streams which are the fastest to treat. They tend to be high in the landscape and so deliver the most miles of wetted channel for the longest time.

PBR also creates more jobs than any other restoration method by focusing on handwork and human power. We’ve got a bunch of people with shovels instead of one guy with a bulldozer, and without any heavy equipment our carbon emissions are very, very low—the last build we did was under 1/2 ton of carbon, door to door, mobilization and everything.

The lack of diesel toys does make it a great workout, but a lot of this work can be done by a reasonably fit high school graduate who loves to get dirty.

And with 40+ million people newly unemployed, there’s never been a greater need for meaningful work at living wages. So there’s a bigger vision here than just driving posts and shoveling mud. I want to get people outside, in the fresh air and sunshine, doing good honest work to restore our watersheds. I really believe that together we can fix our working and wild landscapes, and the new website will reflect this conviction. Coming soon!

The thread starts

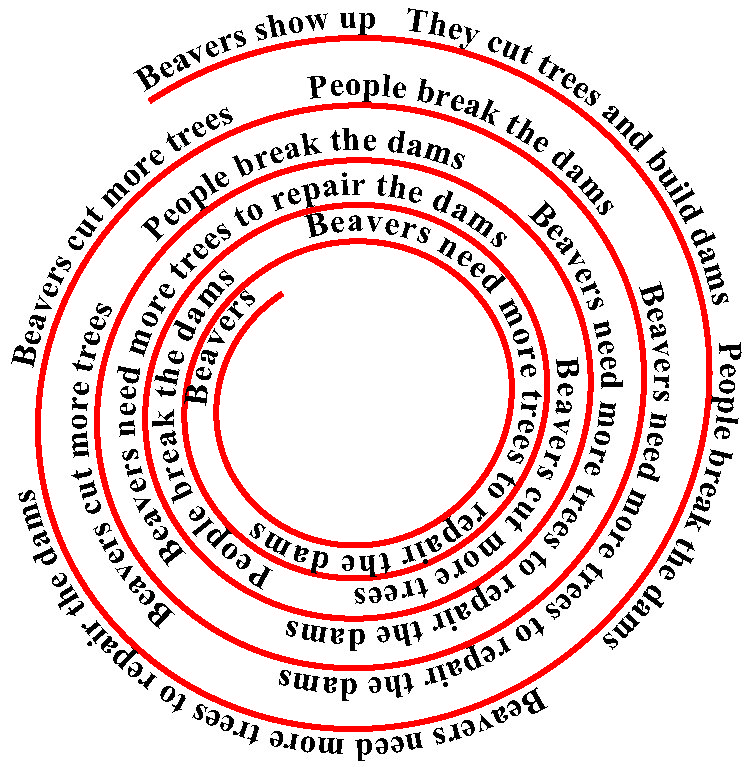

The thread starts  Click the stopwatch at 10 AM with a beaver dam and a flooding problem.

Click the stopwatch at 10 AM with a beaver dam and a flooding problem.

This June I took a multi-week roadtrip to the Methow Valley to work with the Methow Beaver Project at their facility in Winthrop, WA.

This June I took a multi-week roadtrip to the Methow Valley to work with the Methow Beaver Project at their facility in Winthrop, WA.